The Fungi Awakening: A Journey into Mushrooms, Sustainability & Second Sky!

Welcome & Introduction

Welcome friends—old and new! Tonight marks a joyful revival of the Food, Fungi and the Forest community in a new and inspiring home: Second Sky, an eco-conscious gathering space for regenerative culture and creative exchange.

We’re here not just to reconnect over a shared love of fungi, food, forest knowledge, and sustainability—but to spark new relationships and experiences rooted in curiosity, resilience, and reciprocity. Whether you’re a seasoned mycophile or just curious about mushrooms, plants, and ecological living, you belong here.

🍄 1. Fungal Fundamentals: Learning from the Mycelial World

Our evening begins with a gentle dive into the world beneath our feet.

What is mycelium and why is it one of the most important organisms on Earth?

Mycelium is the underground network of thread-like cells called hyphae that make up the primary body of a fungus. While the fruiting body (like a mushroom cap) is the reproductive structure we usually see, it’s just a small part of the organism. Think of it like the apple on an apple tree—mycelium is the tree.

Mycelium acts as nature’s internet—a vast, living, intelligent web beneath our feet that can stretch for miles. It connects trees and plants in what’s called the Wood Wide Web, transferring nutrients, water, and even chemical signals across species. This mutual aid network allows forests to thrive, supporting both young saplings and aging giants (Simard, 2021).

Takeaway: Without mycelium, forests would collapse. It enables ecosystems to regenerate, decompose organic matter, and regulate life cycles on Earth. Fostering soil health means fostering mycelium—so think before you till, and say yes to leaf litter!

📚 Reference:

-

Simard, Suzanne. Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest. Knopf, 2021.

-

Stamets, Paul. Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World. Ten Speed Press, 2005.

How does fungi recycle nutrients, form symbiotic relationships with plants (like mycorrhizal fungi), and even break down toxins.

Fungi are nature’s decomposers, breaking down complex organic materials like cellulose and lignin that animals and bacteria can’t. Without them, dead trees, fallen leaves, and animal waste would pile up endlessly. Through enzymatic action, fungi return these nutrients to the soil, enriching it for new growth.

In addition, around 90% of plant species form mycorrhizal partnerships with fungi. The fungi extend the plant’s root system, improving water and nutrient uptake (especially phosphorus), while the plant shares sugars made through photosynthesis. These symbiotic relationships are essential for healthy plants, resilient ecosystems, and sustainable agriculture.

Fungi can also perform mycoremediation—breaking down environmental toxins such as petroleum, pesticides, and heavy metals. For example, Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushrooms) has been shown to break down hydrocarbons in oil spills (Harms et al., 2011).

Takeaway: When we compost, mulch, or plant companion species that support fungal networks, we’re aligning with the regenerative cycles fungi excel at. They’re the great recyclers—and healers—of the planet.

📚 Reference:

-

Harms, H., Schlosser, D., & Wick, L. Y. (2011). Untapped potential: exploiting fungi in bioremediation of hazardous chemicals. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 9(3), 177–192.

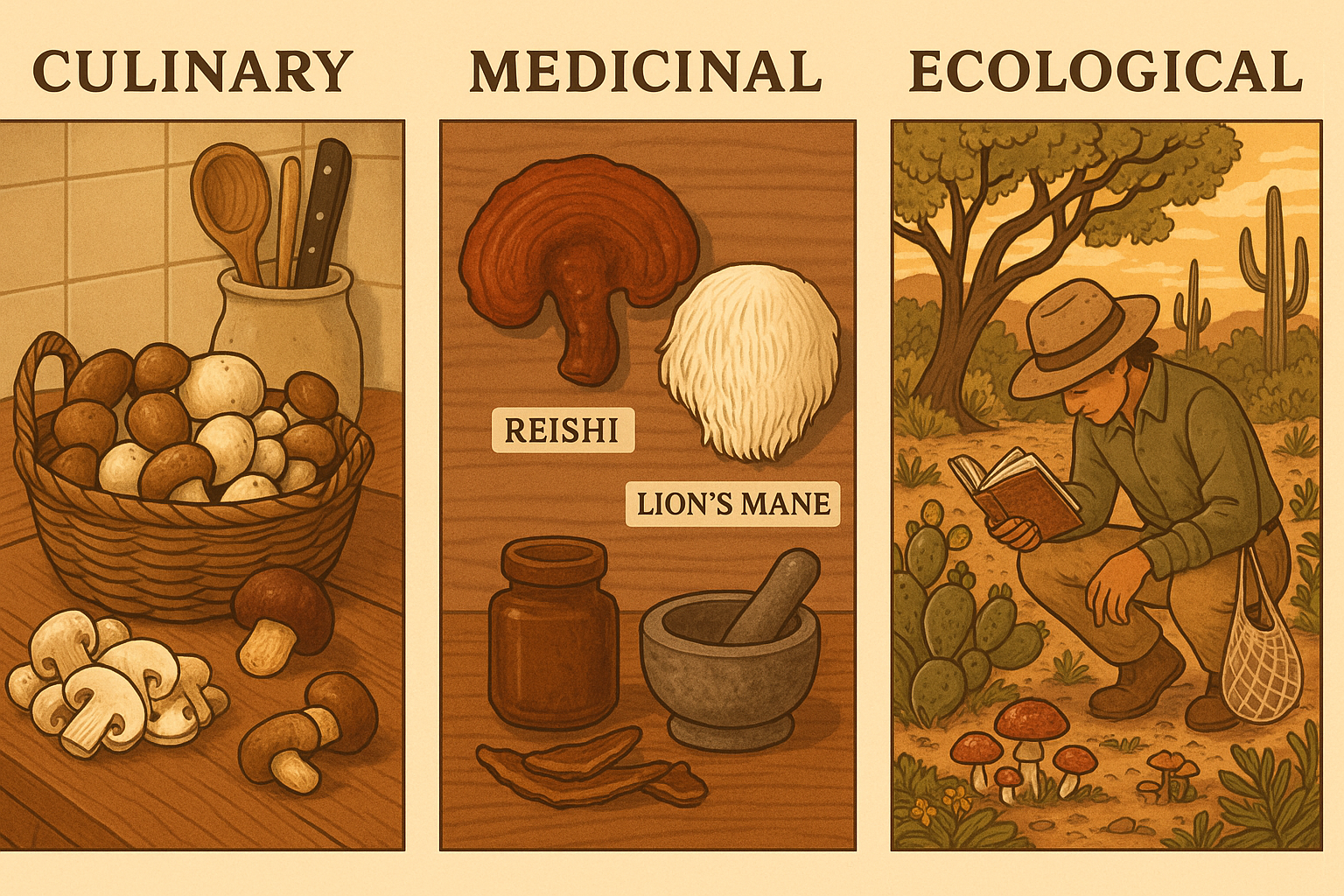

We'll explore the fascinating overlap between culinary, medicinal, and ecological mushrooms—including a brief overview of how to start foraging, growing, or cooking with fungi responsibly.

Mushrooms are not only delicious—they’re nutritional powerhouses and bioactive marvels. Edible mushrooms like shiitake, maitake, and oyster are packed with protein, fiber, B vitamins, and immune-boosting beta-glucans. Others, such as reishi (Ganoderma lucidum) and lion’s mane (Hericium erinaceus), have long been used in traditional Chinese medicine for supporting cognitive health, immunity, and longevity.

Ecologically, fungi improve soil fertility, support plant life, and sequester carbon. Learning to forage or grow your own mushrooms fosters deeper ecological literacy and self-reliance.

Starting points:

-

Foraging: Begin with easy-to-identify species like chanterelles, morels, or turkey tail. Use local field guides and go with a knowledgeable guide. Never forage without 100% certainty of ID—mistakes can be fatal.

-

Growing: Start with mushroom kits or logs for shiitake or oyster. Indoor growing with ready-to-inoculate blocks is great for beginners.

-

Cooking: Always cook wild mushrooms; even edible ones can be tough or mildly toxic raw. Sauté, roast, or dry and powder them for soups and teas.

Takeaway: Responsible fungi use begins with respect—for the ecosystem, for your body, and for indigenous knowledge systems that have long honored mushrooms as food, medicine, and spiritual allies.

📚 Resources:

-

Hobbs, Christopher. Medicinal Mushrooms: The Essential Guide. Storey Publishing, 2020.

-

Arora, David. All That the Rain Promises and More. Ten Speed Press, 1991.

-

Radical Mycology Collective. Radical Mycology: A Treatise on Seeing and Working with Fungi, 2016.

Look forward to hands-on displays and fungal samples for up-close observation.

🌍 2. Sustainability & Climate Resilience

This section focuses on community-based, fungi-informed strategies for a more livable world.

How can mushroom cultivation play a role in waste reduction, soil health, and permaculture?

Mushroom cultivation is a powerful example of circular design in action. Many gourmet and medicinal mushrooms—like oyster (Pleurotus ostreatus), lion’s mane (Hericium erinaceus), and shiitake (Lentinula edodes)—can be grown on materials typically treated as waste: straw, coffee grounds, corn husks, sawdust, and even cardboard. This process diverts organic material from landfills and reduces methane emissions, a major contributor to climate change.

After harvesting, the leftover mycelium-rich substrate—known as spent mushroom substrate (SMS)—can be added to gardens or farms. It improves soil tilth, boosts microbial life, and retains moisture, which is especially valuable in arid ecosystems like the Sonoran Desert. In permaculture systems, mushrooms can be integrated into compost piles, food forests, and hugelkultur beds, supporting plant health naturally without synthetic inputs.

Takeaway: You can grow mushrooms at home or in your garden using local waste streams and then return those nutrients to the soil. It’s a low-tech, high-benefit practice that empowers food independence and ecological restoration.

📚 References:

-

Stamets, P. (2005). Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World

-

Ghosh, R. (2020). “Sustainable Use of Agro-Waste for Mushroom Cultivation and Organic Fertilizer Production,” Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems

Explore climate-smart food systems, water stewardship, and regenerative agriculture practices.

Climate-smart food systems aim to increase agricultural productivity and resilience while reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Fungi are uniquely positioned to support these goals. Cultivating mushrooms requires minimal water, no synthetic fertilizer, and very little land compared to conventional crops. This makes them an ideal food source in regions facing water scarcity and soil degradation.

Moreover, mycelium acts as a natural water sponge—its dense, fibrous network holds water in the soil, slows erosion, and promotes infiltration. When integrated into regenerative agriculture techniques like no-till farming, polycultures, and agroforestry, fungi help build long-term soil carbon stores and nutrient cycling, mitigating climate impacts while enhancing food security.

Takeaway: Whether you’re growing mushrooms, using compost teas with fungal spores, or simply preserving fungal life in your garden soil, you’re contributing to a climate-adaptive food system that can nourish both people and planet.

📚 References:

-

FAO. (2013). Climate-Smart Agriculture Sourcebook

-

Jones, Christine. (2010). “Soil Carbon Sequestration and Fungi in Regenerative Agriculture,” Journal of Soil and Water Conservation

-

Cheung, P. (2013). “Mushroom as Functional Food in Sustainable Diets,” International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition

Hear about local and global efforts that center Indigenous knowledge and land-based wisdom.

Long before “climate resilience” became a buzzword, Indigenous communities across the world had already been practicing it through reciprocal relationships with land, water, fungi, and forests. In many cultures, fungi hold spiritual, medicinal, and ecological significance—seen not just as food or tools, but as kin. For example:

-

The Mazatec people of Oaxaca use Psilocybe mushrooms in sacred healing ceremonies.

-

Siberian and Sámi cultures historically used Amanita muscaria in ritual and shamanic contexts.

-

Pacific Northwest Coast tribes integrated bracket fungi into tool-making, fire-starting, and storytelling.

-

Closer to home, Indigenous desert-dwelling groups like the Tohono O’odham and Yaqui rely on a seasonal ecological calendar that includes fungi, seeds, and rains—an adaptive model for resilience in arid lands.

Today, Indigenous leaders are reclaiming land-based knowledge systems through food sovereignty projects, native seed saving, forest restoration, and cultural mycology education. Supporting these efforts means respecting Indigenous sovereignty, learning with humility, and centering community voice in sustainability conversations.

Takeaway: Regenerative solutions already exist in Indigenous knowledge. We must listen, support, and co-steward responsibly—not as extractors of wisdom, but as allies in restoration.

📚 References:

-

Kimmerer, R.W. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants

-

Whyte, Kyle Powys. (2017). “Indigenous Climate Change Studies,” Climatic Change, 120(3)

-

Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance (https://nativefoodalliance.org)

🍽️ 3. Culinary, Medicinal, and Ecological Mushrooms—And How to Start Foraging or Growing Them Responsibly

Mushrooms are more than just food—they are medicine, teachers, and keystones in ecosystems.

-

Culinary mushrooms like shiitake (Lentinula edodes), lion’s mane (Hericium erinaceus), and maitake (Grifola frondosa) are not only delicious but also rich in protein, fiber, and bioactive compounds.

-

Medicinal mushrooms have been used for centuries in Eastern and Indigenous medicine traditions. Reishi (Ganoderma lucidum) is known for its immune-modulating effects, while turkey tail (Trametes versicolor) is researched for its anti-cancer properties (see NIH trials and studies).

-

Ecological mushrooms such as wood-decomposers or dung-loving fungi are critical to habitat restoration and composting systems.

Foraging responsibly starts with education:

-

Only harvest mushrooms you can 100% positively identify using field guides or apps like iNaturalist or Mushroom Observer.

-

Never take more than you need. Follow the “leave no trace” ethos and harvest in a way that respects the habitat.

-

Join a local mycology group for guided walks and ID training.

Home growing is easier than ever with beginner kits (like oyster or lion’s mane grow blocks) or spore syringes and grain spawn for more advanced cultivation.

Takeaway: Mushrooms nourish the body, mind, and planet. With a little care and knowledge, you can safely explore their incredible diversity and gifts.

References:

-

Hobbs, C. (2020). Medicinal Mushrooms: The Essential Guide.

-

National Institutes of Health (NIH): Studies on Trametes versicolor in cancer patients.

-

Field guides: Mushrooms Demystified by David Arora.

🏞️ 4. Introduction to Second Sky

The vision and values behind Second Sky

The land and facilities: indoor spaces, garden areas, learning zones

Get involved through events, residencies, volunteering, and creative offerings

🎁 5. Surprises & Special Offerings

You never know what might pop up like mushrooms after the rain…

- Raffle prizes and gift giveaways

- A special treat or tasting

- A brief storytelling moment or nature-based reflection

- Maybe even a pop-up art installation or mini plant swap—who knows?

...because surprises are part of the magic of mycelial life.

🎶 6. Special Performance: Mushroom Music

🌟 Closing Thoughts

We hope you leave tonight inspired, grounded, and more connected to this incredible web of life. This is only the beginning—more events, workshops, and myco-magic are on the way. Let’s keep growing, together.

COMING IN AUGUST: